|

Coast Range Tour

1. The

natural environment

2. Humans

in the Coast Range

The natural environment

|

The Coast Range is a major topographic

and climatic divide in the Pacific Northwest region. Its

mountains are rugged with sharp ridges and steep slopes.

Elevations range from 450 to 750 meters (1500-2500 feet)

in main ridge summits, with a high of 1,249 meters (4097

feet) on Marys Peak. |

| Rugged terrain gives way along the coast

and major rivers to undulating hills and flat valleys

where dairy farming is common. The mountain slopes are

typically a mosaic of young forests of different ages,

reflecting the recent historic pattern of forest management. |

|

|

The Coast Range climate is characterized

by mild temperatures, a long frost-free season, prolonged

cloudy periods, narrow seasonal and daily temperature

fluctuations, mild wet winters, cool dry summers, and

heavy precipitation mostly falling from October to March.

The highest precipitation occurs along the interior mountain

range, while the driest areas are near the Willamette

valley. |

| The Coast Range is among the most productive

forest ecosystems in the world, more productive even than

many tropical forests. It has the capacity to produce

huge quantities of wood, but also produces large quantities

of non-timber vegetation, wildlife, and fish, all of which

depend on the same underlying factors: mild climate, abundant

rainfall, and deep soils. |

|

|

Streams in the Coast Range have historically

contained large fallen trees, which created crucial habitat

for salmonids and other aquatic vertebrates and invertebrates. |

In contrast to the productivity of forest

lands, the net primary productivity of streams in the Coast

Range is relatively low, possibly because high forest productivity

means relatively little sunlight reaches the water - less

than five percent of full sunlight in some cases. However,

coast range watersheds have the potential to produce large

amounts of fish biomass as a result of anadromous fish runs.

When these fish, particularly salmon, made their way into

coastal streams in the past, they ended up as carcasses

on the shore, providing a source of food and nutrients for

predators, scavengers, and the ecosystem as a whole.

| While the Coast Range is an ideal region

to grow trees for timber, it is also ideal for species

that use large live and dead trees, and their associated

stream reaches, for habitat. Endangered species such as

the marbled murrelet, the northern spotted owl, and the

coho salmon have inhabited the province for millennia.

|

|

|

Large dead wood has several functions

in Coast Range forest ecosystems, including: fixation

of nitrogen; storage of carbon and water; development

of soil structure; habitat for cavity-nesting and forest

floor vertebrates; and habitat for invertebrates, plants,

and fungi. |

| Disturbances come in many shapes and

sizes in the Coast Range, all integral to the productivity

and biological diversity of ecosystems. Landslides open

gaps in dense forest and expose mineral soils, which may

be important to maintaining some deciduous shrub and tree

species. Landslides also feed large and small materials

into both headwater and mainstem streams, affecting stream

function and productivity. |

|

|

Floods have always played a dramatic

and integral role in shaping streams and riparian zones

in the Coast Range. They can initiate landslides on slopes

that move large and small materials into streams, and

open up forest gaps. In streams, they scour stream beds,

move large amounts of coarse woody debris, carry fine

sediments, rearrange stream profiles, and open up the

forest canopy to allow higher levels of sunlight to reach

the water. |

Until the advent of large-scale logging

and effective fire suppression in the middle of the 20th

century, wildfires were the dominant disturbance in Coast

Range forests. Before Euroamerican settlement, fire return

intervals ranged from 90 to 400 years, with severity ranging

from light to severe (>70% of canopy trees killed). In

its natural state, the Coast Range would have been a slowly

shifting mosaic of large and small patches of forest, ranging

from shrubby areas to dense old forests.

Humans in the Coast

Range

Return to top

|

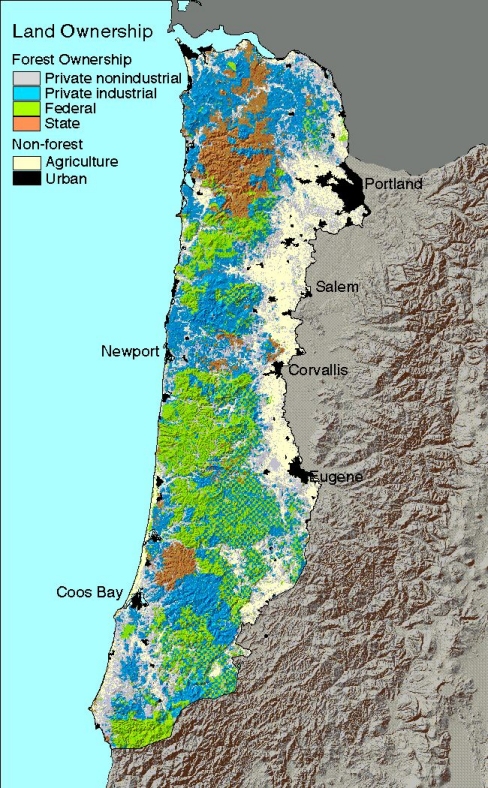

Current forest patterns result primarily

from wildfires and historic and present-day logging.

Virtually all forest lands in the Coast Range in private

ownership have been harvested at least once in the past

and are less than 80 years old.

|

| Many National Forest landscapes retain

the patterns created by two decades of staggering small

harvest units across the landscape and harvesting them

at a constant rate. Many BLM lands have a similar mosaic

of clear cuts, but also frequently appear as a checkerboard

of older forests mixed with young forests on the surrounding

private lands. Logging of older forest on federal lands

was drastically curtailed after listing of the northern

spotted owl as a Threatened species under the Endangered

Species Act. |

|

Private industrial landowners seeking maximum

financial returns on their lands use intensive management

methods that include clearcutting most live trees and snags,

preparing sites with fire or herbicides, replanting with

a single species (usually Douglas-fir), periodic thinning

to maintain vigorous and evenly spaced crop trees, and harvesting

at 40- to 70-year intervals. Clearcut units on these lands

tend to be larger than on federal or state lands, with 120

acres the current maximum allowed under the State Forest

Practices Act.

|

Another view of private industrial lands. |

| Forests on non-industrial private lands

reflect the distribution of parcels of individual landowners,

which are typically much smaller than industrial or federal

lands. These lands are often found along streams, are

usually less intensively managed for timber than industrial

lands, and utilize partial harvesting more often. |

|

|

State lands are generally intermediate

in management intensity between private industrial and

federal lands. Less than 10 percent of the coastal province

is State-owned, with the Tillamook and Elliott State Forests

being the predominant holdings. State forest management

plans and practices are changing to reflect societal concerns

about biodiversity. |

Forest roads have served numerous functions,

including access for extraction of wood and other forest

products, silvicultural activities, fire detection and suppression,

and recreation. Unintended negative impacts have included

effects on water runoff, erosion and effects on fish habitat,

landslide initiation, invasion of exotic species and pathogens,

and wildlife dispersions due to collisions or hunting. Although

roads commonly occupy less than four percent of the area

of a forest landscape, their effects can be more widespread.

|

Forests and farmland in the Coast Range

have historically been subject to development, either

low-density residential or sometimes urban. Although Oregon’s

land use planning program attempts to concentrate development

within urban growth boundaries, its success remains uncertain. |

| Leaving riparian buffers along streams

is now a common approach to protecting aquatic habitat.

However, many questions remain about how wide those buffers

should be, how they should be managed, and how they should

be distributed across a watershed. |

|

|

Recreational uses of the coastal province

are important to the economy and social well-being of

Oregon. The Coast Range, coastal valleys, and beaches

have long attracted visitors to their mix of fishing,

hunting, hiking, birdwatching, beachcombing, cycling,

camping and RV use. Decisions affecting road closures

and forest and wildlife management will have impacts on

recreation opportunities. |

| Community involvement in land use issues

has steadily increased over the last several decades as

forest management controversies have become more intense.

Watershed Councils are examples of collaborative efforts

to reach watershed goals with greater public input. |

|

|